Let’s say it in English: “We are Colombia!”

A gray cloud spread over South Philadelphia. Carlos and I filled our plastic cups with draft beer while a couple leaned against the backyard’s wooden fence and smoked. We ran away from the cold going inside the house passing the kitchen, where three women chatted beside an open closet covered with a net, where Rachel had put her two cats named Kitty and Other Kitty.

On a table pushed against the wall, a man wearing a New York Giants t-shirt loaded up a cardboard plate with tomato sauce meat balls. Rachel came down the stairs carrying her small blond and blue eyed son, who turned his face away when spotting us. The living room was filled with people sitting on a sofa and dining room chairs gathered around a flat screen television that stood against the other wall.

I took some carrots from a tray, while Carlos sat on the floor beside Ali, hugging his girlfriend at the waist. Everybody was watching the last moments of the game that the New York Giants were winning over the New England Patriots. It was the Super Bowl final. I approached the screen thinking about the previews of the historic game: The Patriots had arrived undefeated, something never seen before, but their accomplishment was tainted by allegations of cheating.

“Can you believe this shit? Life’s like that: Shit! How unfair! I don’t know why these things have to happen?” said a Venezuelan guy named Javier, who I had just met that afternoon. He gestured wildly while speaking, glancing at the other party goers with fury, as they viewed the last moments of the game. He opened a closet and put on his jacket, cap, and gloves with sharp motions.

“Are you O.K.?” I asked.

“No, brother, I’m out of here; this makes me sick. You know what they’re called and nobody wants them to win? The Patriots, and that means nothing to these fuckin’ Americans. I don’t even like this shitty sport!” he yelled at them before crossing in front of the TV, going out and slamming the door as the Patriots quarterback made a desperate last attempt, with a great seventy-yard pass that crossed the whole field and was almost caught by one of the receivers who saw the ball drift through his hands.

“The Patriots didn’t deserve to win,” Ali said, walking back home. “Not after the cheating they did at the beginning of the season, when they were caught filming the coaching strategies of another team in the sidelines; justice does exist.”

“In Colombia, we say that the cheater falls into his own pit,” I told them before saying goodbye. The night had fallen and some people were exiting an Irish Pub, singing victory songs.

I headed home thinking that justice limps but arrives. Something similar had happened with McLaren and Ferrari in the previous Formula 1 championship, that Kimi Raikkonen won by one point, after Lewis Hamilton had lead it throughout the year, in spite of the cheating that his team had made when stealing a technical book mid-season from Ferrari.

God! The same thing needs to happen in Colombia, justice must come, it’s time, we all ask for it, I said to myself as I thought of all of the tricks, lies, and crimes that the FARC have been committing in a continuous and unpunished way for years. Innumerable murders returned to my mind, as did the ever-present images of devastated towns, tortured and harassed peasants that end up floating down the stream or buried in common graves. One in particular—a torched church with more than one hundred people inside—reeled through my mind as if I had just seen it on the news. I thought about the explosion of a car bomb in a social club, the explosion of two grenades in a bar filled with students, the images of a bicycle bomb, a necklace bomb, a donkey bomb, young people and soldiers mutilated by land mines, death, blood, corpses and disjointed men scattered on the floor. I pictured the desolation of hundreds of kidnapped people during endless years of captivity, living in the jungle under subhuman conditions, ill with leishmaniasis and parasites, or the fear and rage of cattle dealers and businessmen while being extorted or running the risk of seeing one of their children become victim of a murder attempt, when they had the courage to say: "I’m not giving one peso to those assassins."

As I finished walking the blocks that led to my apartment in center Philly, a harmless bum with a canvas bag slung over his shoulder asked me for a match to light a cigarette.

“I don’t smoke” I told him and continued my way, analyzing Javier’s reaction to the name of the New England team, thinking that it’s not words that make men, but it’s their acts which speak for them, and that beyond being the denomination for a man who loves his country, a true patriot is someone that wants what’s good for his nation. I went to bed asking myself: What can be more unpatriotic than cheating, lying, blackmailing? Words all united by badness, the intention to take advantage of, harm, or damage someone else. What good could a group that robs, extorts, tortures, kidnaps, assassinates and massacres the civilian population want for its country? What good does a group want, when it perpetuates terror shielded in a political flag while it profits from drug trafficking, kidnapping, and the sale of human beings?

I fell asleep imagining the protest marches that would be carried out on the following day, knowing as it’s always been known, that the façade in which the FARC is shielded is pure shit. It has been pure shit for many years.

I woke up early the next day, and went to work. Once the time of the protest arrived, I said bye to my coworkers and walked out of the student center and onto the street. At 11:45 a.m., I arrived on Broad. It was cold, but not enough to make me take my cap and gloves out. My friend Eduardo was across the street at our meeting point, in front of Wendy’s. He took a step to one side, went back, and took another step towards the other side, with his tall and strong tennis-player body. He held a cell phone to his mouth, speaking naturally, with comfort. He took his hand out from his coat pocket when he saw me and waved; then he returned to his conversation.

The cars passed with their lights on. Some turned on Cecil B. Moore, switching off their blinkers. The traffic light changed and a sharp sound like the singing of an amplified pigeon, resonated from one side of the street to the other, repeating every second. A young man about twenty, wearing brown linen trousers and a blue cotton jacket, threw himself down on the street, moving his thin aluminum cane from side to side. His steps were so fast and confident that we approached the center of the wide street at the same time. The sound of his cane striking the floor methodically—tac-tac-tac-tac, could easily be heard over the sharp noise of the crosswalk light. I glanced at him as I approached, focusing on his eyes that stared off into space. They were blue and his pupils shone.

To my left, I saw City Hall in the distance over the mist, with its gray limestone tower, its second French empire architecture, its enormous clocks, greater still than those of the Big Ben in England, and the bronze statue of William Penn, perched on top of the gothic dome, surrounded by contiguous skyscrapers, like a dumb watchman of the city and its inhabitants.

It was a normal day, like any other Philadelphia winter Monday. Some people took the C bus line towards the city center, students wearing jackets, jeans, boots and backpacks on their shoulders rose from the subway station, walking towards their classes, City View Pizza and the other nearby restaurants prepared to receive their first lunchtime clients, two men went in the Bank of America through its glass doors, one left the Barnes & Noble bookstore holding plastic bags in his hands, while some other people drank coffee in Starbucks, and an African American man with a fluorescent orange vest on top of a heavy dark coat sold newspapers in the corner, lifting them in front of his face, to show a photo of some momentary hero of the New York Giants’ victory over the New England Patriots.

Eduardo took his hand out from his pocket to shake mine. He spoke on his cell phone for a few seconds, striking the air with small kicks he gave with the point of his sneaker, as he stretched his long leg.

“My friend could not get out from work,” he told me after he hung up. “Andrés can’t come either; he’s in class. Who else are we expecting?” he asked, looking at me with certain deception that his likeable face pronounced, as his head leaned towards one side and his eyes raised slightly.

“A friend of mine from Bogota. She’s coming on the subway; she’ll be here any second now. I can’t stay long, as I’ve escaped from work.”

“Me either, I’m training.”

A pair of women went down the stairs opposite to the orange Cecil B. Moore station-sign, holding a steamy bag of French fries that they had bought in Wendy's.

“I don’t know what’s going on with Beatriz,” I told Eduardo before feeling the vibration of the phone in my pocket. It was her.

“I’m already here, in Fern Rock station,” she said.

“Beatrix, I said in the direction of Fern Rock, not Fern Rock station! Go back one station to Olney, we’ll pick you up there. Thank God it’s on the way. Wait for us on Broad south corner.”

We walked towards the car in front of a gray building with big doors and large windows. The wind struck the red Temple University banners placed on each post, making them flap with violence. The noise of the rippling cloth was like that of a kite.

We went up Norris Street, where the ochre-colored bricks from the "Ghetto" houses contrasted with the skeleton branches of the trees.

“The Colombians went marching in Tokyo even though there’s one of the worst snows in history; and in Melbourne there were more than 500 people, my friend told me,” said Eduardo.

“There are simultaneous marches in all the great cities of the world. Isn’t that something demonstrative?”

“It’s without precedent,” he answered as we entered the car under the look of two African American men who examined us, as they spoke of some business they had between them. I undid the steering wheel lock and turned the engine on, seeing the dirty walkways that appeared filled with papers and plastic bags that the wind dragged across the ground, next to some two and three floor houses, sealed with nailed tables over doors and windows.

“In Colombia, they’re thankful to Chávez for having united the people like this. There are millions marching against the FARC in different cities of the country and the world. It seems as if Colombians are finally waking up,” said Eduardo.

“It was about time”.

“But did you know what Chávez said? That all these attitudes are warlike aggressions against the Liberators army,” Eduardo said.

“If that’s true, Chávez is smoking weed,” I countered.

We went down Diamond, and then headed north up Broad. Camilo was waiting for us on Ontario, in front of the Temple University hospital, located a mile and a half away. We hurried in between the flow of the traffic, stopping in front of repeated traffic lights that studded the avenue.

“Who knows how many people there are in New York and Washington? In Miami there’s thousands? The FARC is hated worldwide?”

“Eduardo, that doesn’t matter to them. The Guerrilla is a business; everybody knows it”.

“It’s going to have to matter. The entire world is finding out that the people from Colombia hate them”.

We wove between cars as we approached the University hospital and my watch displayed 12:05 a.m. I accelerated, but the light turned red, and I was forced to stop.

“Thank God that it’s a demonstration rather than a march; if not, it would have already left us behind,” I said, looking at a vacant lot filled with construction waste.

We went under a railroad bridge that crossed Broad diagonally, advancing on some other streets where warehouses and buildings with dirty and peeled facades rose on either side. Soon after, we arrived at Ontario.

Camilo got into the car with a friend who was wearing a cap, a jacket, and a white poncho with the Colombian tricolor. The light clothing contrasted with his brown colored skin and his three-day beard, which had grown in the edges of his moustache.

“Carlos Barrero, nice to meet you,” he said.

“Eduardo Bechara.”

“Camilo Moncada.”

“Eduardo Saavedra.” We shook each others hands.

“All the protests worldwide have just begun,” Camilo said with excitement. “Paris, London, Amsterdam, Rome, Madrid, Berlin, Moscow, Oslo, Stockholm, and many other European cities already had their marches”.

“It seems that there are protests in the most remote places of the planet: The Sahara desert, the Patagonia, Angola, Kurdsistan. People are speaking of a global repudiation.”

“That’s not amazing, Colombians are everywhere in the world,” Eduardo said, leaning his head forward.

“Are you from Cali?”

“Yes, you guys?” Eduardo asked.

“Bogota and Pereira.”

I sped, trying to pass cars in the increasing traffic. The gray horizon threatened rain.

“What do you guys study?”

“A PhD in biochemistry. We’re working on an investigation project, experimenting with rats on the effect nicotine has as an inhibiting agent of pneumonia. You also study at Temple?” Camilo asked.

“Administration and I’m on the University tennis team. This weekend we play against Penn. Hey, isn’t it incredible that this movement of millions of people was organized through Facebook?” said Eduardo.

“That’s because it’s an initiative by the young people with their hearts, without having stingy political interests of any kind,” I said.

The traffic grew worse as we approached Olney, where Beatriz waited for us. I saw her between the crowds of people that crossed the street even though they did not have the right-of-way. Her face cheered when she saw us. I turned and pulled over onto the bus lane, next to different stores that bordered the two way street.

“You get confused so easily, Beatriz,” I said.

“What can I do, I’m new to Philly. Isn’t this incredible? All the Colombians of the world united against the FARC. It’s something so extraordinary that it’s almost unbelievable.”

“Yes, it’s extraordinary,” I said.

“Nobody wants them anymore. The Guerrilla soldiers that handed themselves in before the government one week ago said that they never wanted to go back to live that torture”.

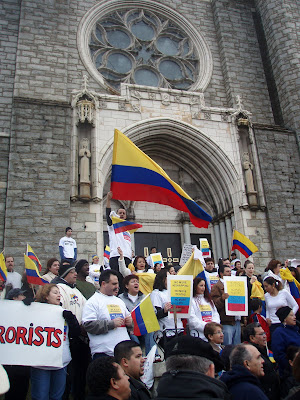

Beatriz smiled; she wore a gray Penn sweatshirt and a long jacket that reached her knees. I hadn’t seen her for a couple of years ago, but she was still as spontaneous as ever. She laughed, opening her black and vivacious eyes as she clasped her hands in front of her mouth. She was surrounded by people of her country, as if part of her land would have extended through the American continent, all the way to the cold Pennsylvanian territory, where the necessity to reject the atrocities of the FARC united her to that national outcry which took us to ignite an inactive nationalism, that erupted even though we were not in our land, but turning onto fifth street, where we saw the Church of the Incarnation. The front of it was packed with people wearing white t-shirts over coats and jackets, flags waving from all sides, camcorders, cameras, reporters and slogans that we listened as we approached, and the blood in our bodies started to run faster.

Chronicle published in El Tiempo Colombian newspaper http://www.eltiempo.com/ on February 5, 2008.